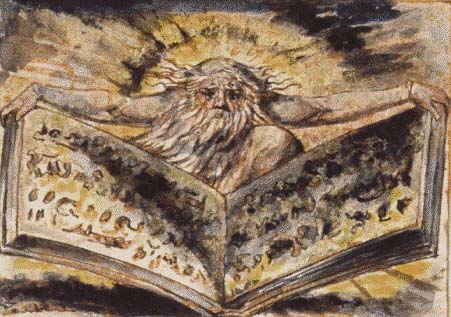

according to Mortimer Adler

ANYONE WHO DESIRES TO LEARN NEED ONLY PICK UP THE BOOK AND READ;

IT IS THAT SIMPLE.

ANYONE WHO DESIRES TO LEARN NEED ONLY PICK UP THE BOOK AND READ;

IT IS THAT SIMPLE.

from "Only Adults Can Be Educated", interview of Mortimer J. Adler with Max Weismann, in "Philosophy is Everybody's Business: Journal of the Center for the Study of The Great Ideas", Vol 3, No 1, 1996.

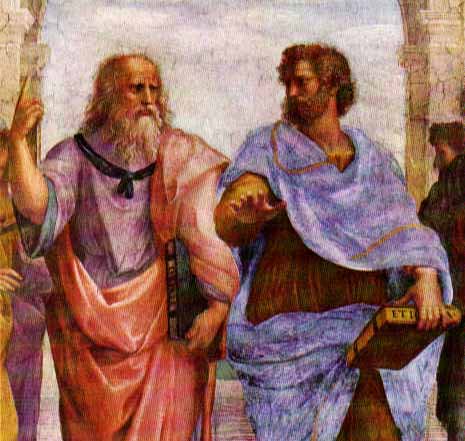

Suppose there were a college or university in which the faculty was thus composed: Herodotus and Thucydides taught the history of Greece, and Gibbon lectured on the fall of Rome. Plato and St. Thomas gave a course in metaphysics together; Fracis Bacon and John Stuart Mill discussed the logic of science; Aristotle, Spinoza, and Immanuel Kant shared the platform on moral problems; Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke talked about politics.

You could take a series of courses in mathematics from Euclid, Descartes, Riemann, and Cantor, with Bertrand Russell and A.N. Whitehead added at the end. You could listen to St. Augustine, Aquinas and William James talk about the nature of man and the human mind, with perhaps Jacques Maritain to comment on the lectures.

In economics, the lectures were by Adam Smith, Ricardo, Karl Marx, and Marshall. Boas discussed the human race and its races, Thorstein Veblen and John Dewey the economic and political problems of American democracy, and Lenin lectured on communism.

There might even be lectures on art by Leonardo da Vinci, and a lecture on Leonardo by Freud. A much larger faculty than this is imaginable, but this will suffice.

Would anyone want to go to any other university, if he could get into this one? There need be no limitation of numbers. The price of admission -- the only entrance requirement -- is the ability and willingness to read and discuss. This school exists for everybody who is willing and able to learn from first-rate teachers.

Why read Great Books?

Posted by Mortimer J. Adler on Wednesday, 2 April 1997

I would like to share with you a letter that I recently received and my answer to it:

Dear Dr. Adler,

Why should we read great books that deal with the problems and concerns of bygone eras? Our social and political problems are so urgent that they demand practically all the time and energy we can devote to serious contemporary reading. Is there any value, besides mere historical interest, in reading books written in the simple obsolete cultures of former times?

People who question or even scorn the study of the past and its works usually assume that the past is entirely different from the present, and that hence we can learn nothing worthwhile from the past. But it is not true that the past is entirely different from the present. We can learn much of value from its similarity and its difference.

A tremendous change in the conditions of human life and in our knowledge and control of the natural world has taken place since ancient times. The ancients had no prevision of our present-day technical and social environment, and hence have no counsel to offer us about the particular problems we confront. But, although social and economic arrangements vary with time and place, man remains man. We and the ancients share a common human nature and hence certain common human experiences and problems.

The poets bear witness that ancient man, too, saw the sun rise and set, felt the wind on his cheek, was possessed by love and desire, experienced ecstasy and elation as well as frustration and disillusion, and knew good and evil. The ancient poets speak across the centuries to us, sometimes more directly and vividly than our contemporary writers. And the ancient prophets and philosophers, in dealing with the basic problems of men living together in society, still have some thing to say to us.

I have elsewhere pointed out that the ancients did not face our problem of providing fulfillment for a large group of elderly citizens. But the passages from Sophocles and Aristophanes show that the ancients, too, were aware of the woes and disabilities of old age. Also, the ancient view that elderly persons have highly developed capacities for practical judgment and philosophical meditation indicate possibilities that might not occur to us if we just looked at the present-day picture.

No former age has faced the possibility that life on earth might be totally exterminated through atomic warfare. But past ages, too, knew war and the extermination and enslavement of whole peoples. Thinkers of the past meditated on the problems of war and peace and make suggestions that are worth listening to. Cicero and Locke show that the human way to settle disputes is by discussion and law, while Dante and Kant propose world government as the way to world peace.

Former ages did not experience particular forms of dictatorship that we have known in this century. But they had firsthand experience of absolute tyranny and the suppression of political liberty. Aristotle's treatise on politics includes a penetrating and systematic analysis of dictatorships, as well as a recommendation of measures to be taken to avoid the extremes of tyranny and anarchy.

We also learn from the past by considering the respects in which it differs from the present. We can discover where we are today and what we have become by knowing what the people of the past did and thought. And part of the past -- our personal past and that of the race -- always lives in us.

Exclusive preference for either the past or the present is a foolish and wasteful form of snobbishness and provinciality. We must seek what is most worthy in the works of both the past and the present. When we do that, we find that ancient poets, prophets, and philosophers are as much our contemporaries in the world of the mind as the most discerning of present-day writers. In fact, many of the ancient writings speak more directly to our experience and condition than the latest best sellers.