FREEDOM IN SERBIA AND THE INTERNET

Serbians demand that the authoritarian government of S. Milosevik respect their will.

Tyrants beware!

On Friday February 22, 1997, Belgrade's first non-Communist in a half-century took office after weeks and weeks of protests against the oppressive regime of Serbian President Slobodan Milosevik. "Democracy is sometimes painful, but patience and tolerance, the will of the majority, are bound to win," said Zoran Djindjic, Belgrade's new mayor. Cyberspace became a new weapon in the war for freedom worldwide and was absolutely vital in fighting the oppressive government of Milosevik and his desire to muzzle free speech and thwart the will of the people. We are just beginning to see the beginnings of democracy in Serbia, and Djindjic and his three party coalition with Vuk Draakovic have not been able to peacefully govern together. Serbia is a long way from being a stable liberal democracy, but a start has been made.It all began when Milosevik voided local elections after his party lost them at the beginning of 1997 and thousands of demonstrators for more than three months took to the streets of Belgrade, calling for an end to the longest-ruling authoritarian government in Europe. Students and opposition leaders wanted Milosevic to recognize opposition victories in November elections in Belgrade and 13 other cities and towns. The protesters - mostly students - made great efforts to protest peacefully and not provoke violence with the police as they blocked traffic, pelted government buildings with eggs and rocks, etc. The government attempted to muzzle the independent media and cover up the protests.

After first trying to ignore the massive protests, Milosevic's propaganda machine went on the offensive. The only nationwide television station, the state-run Radio Television Serbia (RTS), or TV Belgrade, dismissed demonstrators as terrorists, vandals and a handful of desperate people. Finally, the nation's last vestiges of independent media - wily, under-powered competitors of TV Belgrade scattered throughout the Balkan nation - were forced off the air in early December of 1997.

And following the lead of the democratic opposition and students, Radio B-92, one of the independent radio stations reporting on the protests whose signals were jammed, broadcast its news bulletins over the Internet. They quickly moved their webpages to web servers in the Netherlands United States where the Serbian government censors proved helpless to stop them. "They have tried to control us, but we were really fast," said Drazen Pantic, B92 Internet director. "We opened something that didn't exist." The station's ingenuity generated more publicity than B-92 could have imagined, and 51 hours after its airwaves went black, Radio B-92 was reinstated. "Was shutting B-92 down the best thing that ever happened to B-92?" Sasa Mirkovic, the station's director, asked rhetorically. "I could say that, you know, because it mobilized us to use the Internet in a completely different way." The government - while helpless to stop them was not pleased: at least one cameraman for the station was beaten and sustained several bruises. Police beat protesters in the almost nightly protests in the capital of Belgrade. Student leaders pleaded for restraint by the protesters - as long as the protests remained peacefully, the students had the moral high ground. Violence only brought more sympathy to the pro-democracy protesters.

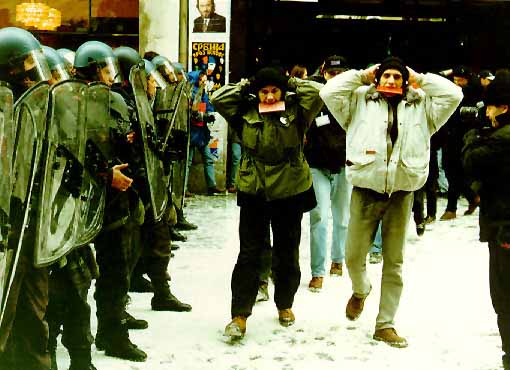

Protesters raise hands high to symbolize peaceful intentions

as they walk by police blocking their way in Belgrade.

Independent Radio B-92 broadcast successfully all throughout the crisis to the rest of Serbia and to the outside world. The people - and the outside world - remained aware of the pro-democracy protests and the government actions to stop them. Pro-democracy activists received many thousands of e-mails supporting their struggle (many from me when the things looked especially rough) and millions stayed in touch with the situation on the World Wide Web. After more than three months, Milosevik finally relented and let the democratically-elected Zoran Djindjic assume the mayorship of Belgrade. This is only the first blow. I am confident that the Internet will prove to be what the VHS videotape player was to Eastern Europe behind the Iron Curtain: a lifeline and source of information to people whose government would like to control their thoughts and view of the outside world and foreign ideas. This rightly scares the heck out of dictators and their lackeys who rule without the consent of their people and who with good reason fear for their futures.

Just wait and see what happens in the future!

No government can control the Internet!

Long live free speech and the flow of information!