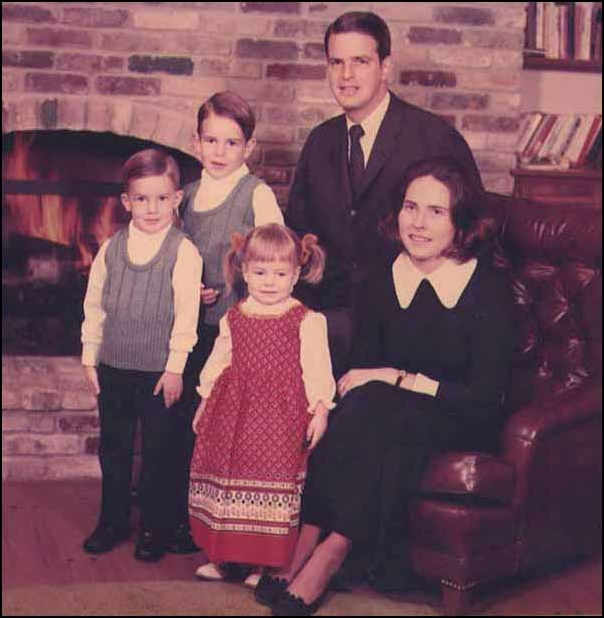

My grandma, Margaret (“Peg”) Harriet Sullivan Geib, died when she was 77-years old.

Her husband, Phillip James Geib, my grandfather, died at 90-years of age.

Their deaths could not have been more different. My grandma was ready to go. I remember her telling me around 1977 or so that she had little interest in the flashy new supersonic Concord passenger jet making news at the time, or any of the popular Atari video games or whatever. My grandma was done. Metaphorically, she had her bags packed and was ready to exit this vale of tears.

And not long after that she had a heart attack. It was not fatal, and all her children and many loved ones flew to Piedmont, California to visit her in the hospital. My grandma received her many visitors in her hospital bed, appreciated their concern, and was surrounded by love. A few days later she had another heart attack in her sleep and died in that hospital bed.

That is about as good a way to go as I can imagine: surrounded by love, dying in her sleep. Not bad. But my grandma was only 77-years old at the time which seems a bit premature. She died too young. I remember at her funeral watching my grandpa kneel in front of her casket in an elegant move of old-world gallantry.

My grandfather, on the other hand, lived too long. He survived his wife by some 13-years. But his body lived beyond what his brain could match, and by the last three or so years he suffered from severe dementia. At the end my grandpa was sitting in a diaper, and he hardly knew his own name; he was miserable, but he was hardly able to articulate his unhappiness. It was a relief when my grandpa finally died. Perhaps he was the most relieved of all? He had lived only too long.

We don’t directly get to choose the time and manner of our dying. But indirectly we do. My grandpa was a paragon of provident living. My grandma was not. It makes sense one of them would live longer than the other.

But genes will have their say, too.

Our birthday is well known to us. The beginning. But our death day will be no less real or important. The ending. The alpha and the omega.

We have no control over our births. We have some control over our death, but not total control.

As I write these paragraphs I realize I have already written about this back in 2018.

It must be much on my mind.

I think a lot about the deaths of members of my family.

Why?

Because so many of the members of the generation above me – my father, mother, stepmother, uncles, aunts, acquaintances – are approaching their deaths. It might be impolitic to say, but it is true. Nobody lives forever. Especially not people in their 80s. It is childishness to pretend otherwise.

So what do I do?

I wait for the horrible phone call announcing the bad news. About once every other year that call comes. It is sudden and dramatic. “So-and-so passed away last night.” “So-and-so was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease.” “So-and-so is undergoing treatment for pancreatic cancer.” The sharp painful memory of the phone call in 1995 announcing the X-ray discovery of the cancerous tumors in my mothers lungs stays with me still. It would not be the last such call. There will be more. When will the next one arrive?

I await it. Sooner or later, it will come.

I have always loved the following poem by Robert Graves about romantic love and eventual loss:

"COUNTING THE BEATS" by Robert Graves You, love, and I, (He whispers) you and I, And if no more than only you and I, What care you or I? Counting the beats, Counting the slow heart beats, The bleeding to death of time in slow heart beats, Wakeful they lie. Cloudless day, Night, and a cloudless day, Yet the huge storm will burst upon their heads one day From a bitter sky. Where shall we be, (She whispers) where shall we be, When death strikes home, O where then shall we be Who were you and I? Not there but here, (He whispers) only here, As we are, here, together, now and here, Always you and I. Counting the beats, Counting the slow heart beats, The bleeding to death of time in slow heart beats, Wakeful they lie.

I love that final line of the poem – “wakeful they lie” – the image of that intimate moment stays with me. It reminds me of my parents who were married for almost three decades before one of the two got cancer and died, leaving the other heartbroken and alone.

She died of lung cancer when she was 55 and he was 57-years of age.

John Irving in his novel “The World According to Garp” similarly talked about the arrival of tragedy as the “under toad” (ie. the undertow of the ocean tides), the feared amphibian which would suddenly seize and pull you under the sea. It is the image of impending tragedy, misfortune which while hidden looms ever-present nearby. Sooner or later, if you wait long enough, it will get you. The “under toad” finally arrived in “Garp” when their youngest son was killed in a tragic car accident involving the infidelity of the mom. The fear of the “under toad” in that novel is pure symbolism: nothing other than anxiety over death and misfortune which always pulls at us, unseen. It is always there, just like the tide pulling you out to sea. But only occasionally does it arrive and drown you, or someone you know. I too have learned to fear the “under toad” – not so much for myself, but for others (and especially my daughters). Death is patient. Time is on its side. You will get that phone call in the middle of the night. The “under toad.”

All this aging and decline. Tragedy and heartbreak. These deaths and rumors of death. It is dark stuff.

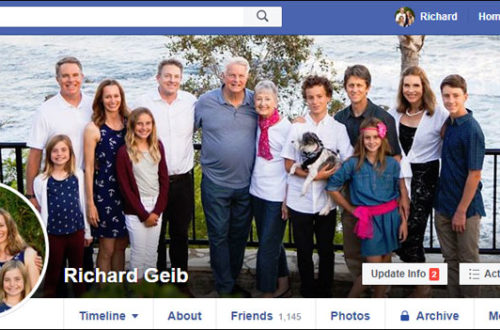

But there is the opposite side of the coin. There are my two daughters, 12 and 15-years old. And my three nephews and nieces of a similar age. And to a lesser extent, my students. There one finds youth and life. They are the future. There is growth and opportunity and energy and potential. True, there is also much that is negative which comes with youth: brashness, impatience, angst, and unwisdom. But that is natural and will ebb with time, too. People grow up. They have been doing it for ages.

And my daughters, too. They will be watching me with apprehension as I decline. Children have been watching their parents age for a long time, too.

So it goes. As the Bible says: “One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth forever.”

I must do my best as a son and a father to play my part in the inter-generational drama which is family.

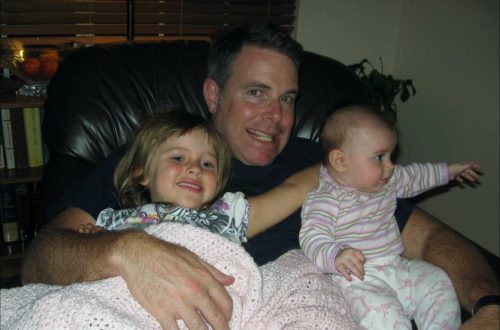

My daughters, in particular, get one chance at their childhoods. I must do my best to make it memorable.

But I must also try to avoid doing too much. Last thing I want to do is be a “helicopter parent.”

I have seen a particular sort of contemporary upper-middle class mom who makes their kids the principal passion and investment in their life once they become pregnant with them. Then their over-parented child gets into Princeton or Yale eventually, and it is the crowning achievement of their life; it validates the last 18-years of their adult lives as a parent. I can see a kid with such an over-invested parent saying in response, “Mom, you need to get your own life!” No child wants to feel the burden of having taken over the life of a parent. No child wants to feel the responsibility to live up the exalted expectations of such a parent. “I dedicated my life to you!” That is a “gift” which comes with strings attached. No thank you.

My father tread a pretty good middle-ground in his involvement in my life, paying attention and being involved with me while still having his own career and pursuits. His adult life did not revolve only around his children. He had his own life. I respected that. Last thing I wanted was for my dad to nail himself to the cross of my upbringing. I suspect my daughters feel the same way about me.

So I will try to meet Aristotle’s Golden Mean and avoid the extremes: of being too involved as a parent, and not being involved enough.

How much of life is trying to navigate unhealthy extremes and finding the Golden Mean? And then examining how things might change over time and what adjustments to make? How much change? How much continuity?

Well, wish me luck, dear reader.

It won’t last forever.

My family.

My life.

“One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.”

Ecclesiastes 1