My younger daughter came up to me yesterday morning as I was eating breakfast and told me breathlessly, “Daddy! The schools in Florida are going into lockdown again. There is bird flu spreading rapidly there!”

Having had her school locked-down and her fourth and fifth-grade school years essentially canceled back in 2020, my daughter was sensitive it might happen again. The trauma of those days returned when she heard this dramatic news on social media. She was alarmed.

Knowing more about the larger context of locking down schools than her, I was highly skeptical. After the disaster of closing schools during the COVID-19 lockdowns, I was pretty sure nobody was going to do that again – especially in Florida with a Republican governor, which had resisted lockdowns back three years ago.

But who knows? Maybe something drastic had happened overnight while we were sleeping.

I did some independent research and I did discover isolated Florida schools locking down temporarily because of specific threats of violence to individual campuses in the past few months. But I found nothing about disease and closing schools system-wide. If something like this was happening in Florida, it would be covered by legitimate news sources.

“Where did you hear about this?” I asked my semi-panicky daughter.

“I saw it on TikTok!”

“Oh, that is nonsense,” my wife countered.

“It’s true! Everyone in the comments of this TikTok video is saying it’s true!” my daughter argued.

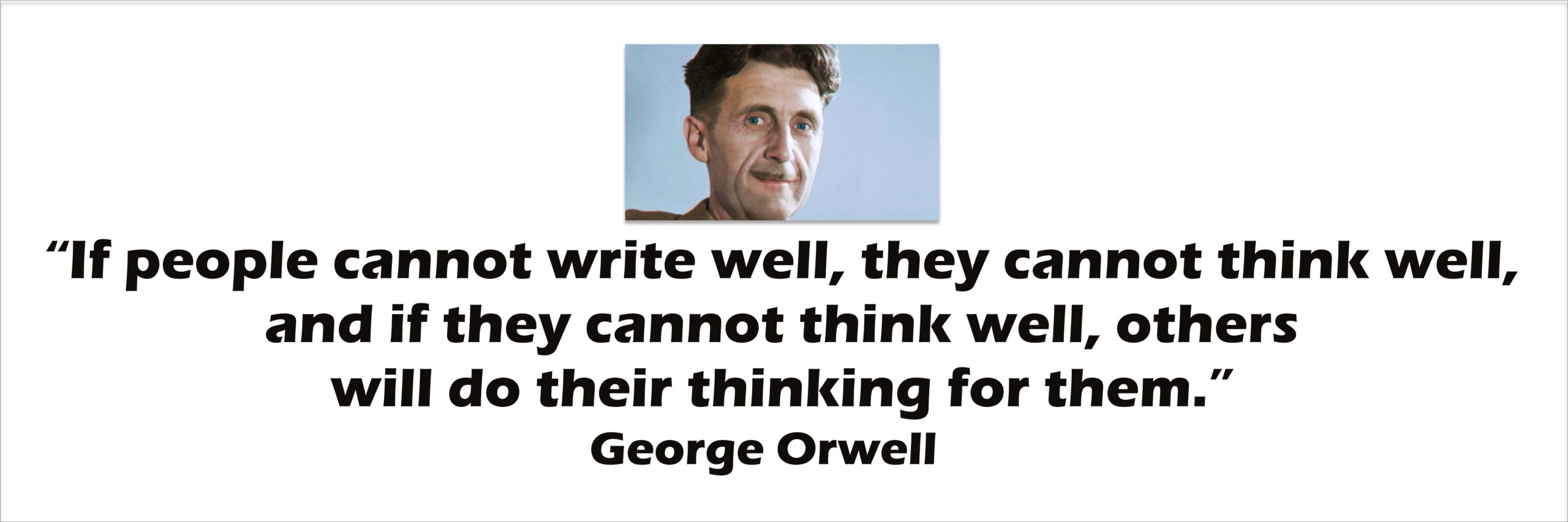

I thought to myself, “Oh my God, I need to talk to my daughter about Internet misinformation, viral memes, and software algorithms!” I need to show her the “Pizzagate” conspiracy, and so many of the other examples of Internet viral rumors which circulate. In the age of social media a lie can travel around the world several times before the truth can get out of bed and put its shoes on. I need to talk to my daughter about independent research, information skepticism, and thinking for oneself. The newest quote I’m going to put on my classroom wall is this:

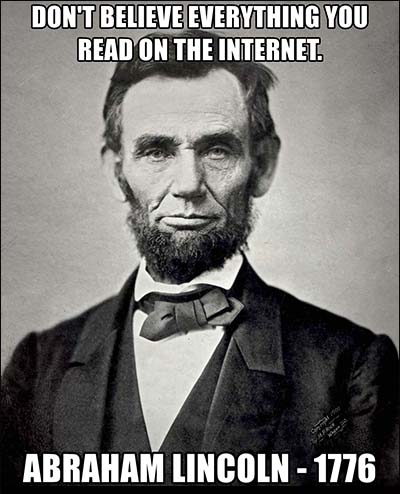

Orwell is so right. So we watched this video from PBS NewsHour about the avian flu outbreak together, and we talked about it. We searched Google for other pertinent information about viral outbreaks in Florida from reputable news sources. My daughter quickly could see that the bird flu was not a dangerous viral outbreak for the species Homo sapiens, at least not at this time, and schools across Florida were not locking down to prevent its spread in a pandemic like we just lived through with COVID-19. I hope my daughter never forgets that feeling of appearing foolish and being taken in by a rumor spread by social media via the Internet. It was a good “teachable moment.” Maybe my daughter can even raise the alarm when her friends or anyone else spreads some similar online information which seems suspect. She can help spread the famous Internet meme from President Lincoln about the dangers of naivete online:

A healthy sense of information skepticism does not come from nowhere. Parents nowadays need to teach their kids how to differentiate fact from fiction online. It is not a skill set they are born possessing; they need to be taught explicitly how to do it. The whole incident illustrated how vulnerable a 7th grader like my daughter is to snake-oil rumors and slippery misinformation online in a rumor-mongering social media world where echo chambers are the norm. Rather than be manipulated this way or that by clever information hucksters online, I would have my daughters learn to think for themselves and research and seek the truth independently.

Over many years I have written about my struggle to keep my kids, especially when they were younger, protected from so much of the manipulating marketers and mindless distraction of the modern mass media. I chose not to have cable TV pumped into my house, and my daughters have almost never seen the inane TV commercials or dumb TV shows which I thought were so harmful when I was growing up. My motto, ever since I was in college, was “Kill Your TV.”

But here’s how that morphed over the years as I became a family man:

“Kill Your TV, Twenty Years Later”

November 13, 2015

But then TV, as I knew it sort of died, and in its place YouTube and other social media actors took its place. Over time, I sort of felt that YouTube was killing me, especially during the COVID pandemic and lockdowns, as a dad I came to see myself defeated by the mass media messages coming into my daughter’s brains:

“‘Kill your TV’? I Count Myself ‘Killed’ by YouTube”

October 1, 2020

Yes, technology, myself, and my family had had a long complicated relationship.

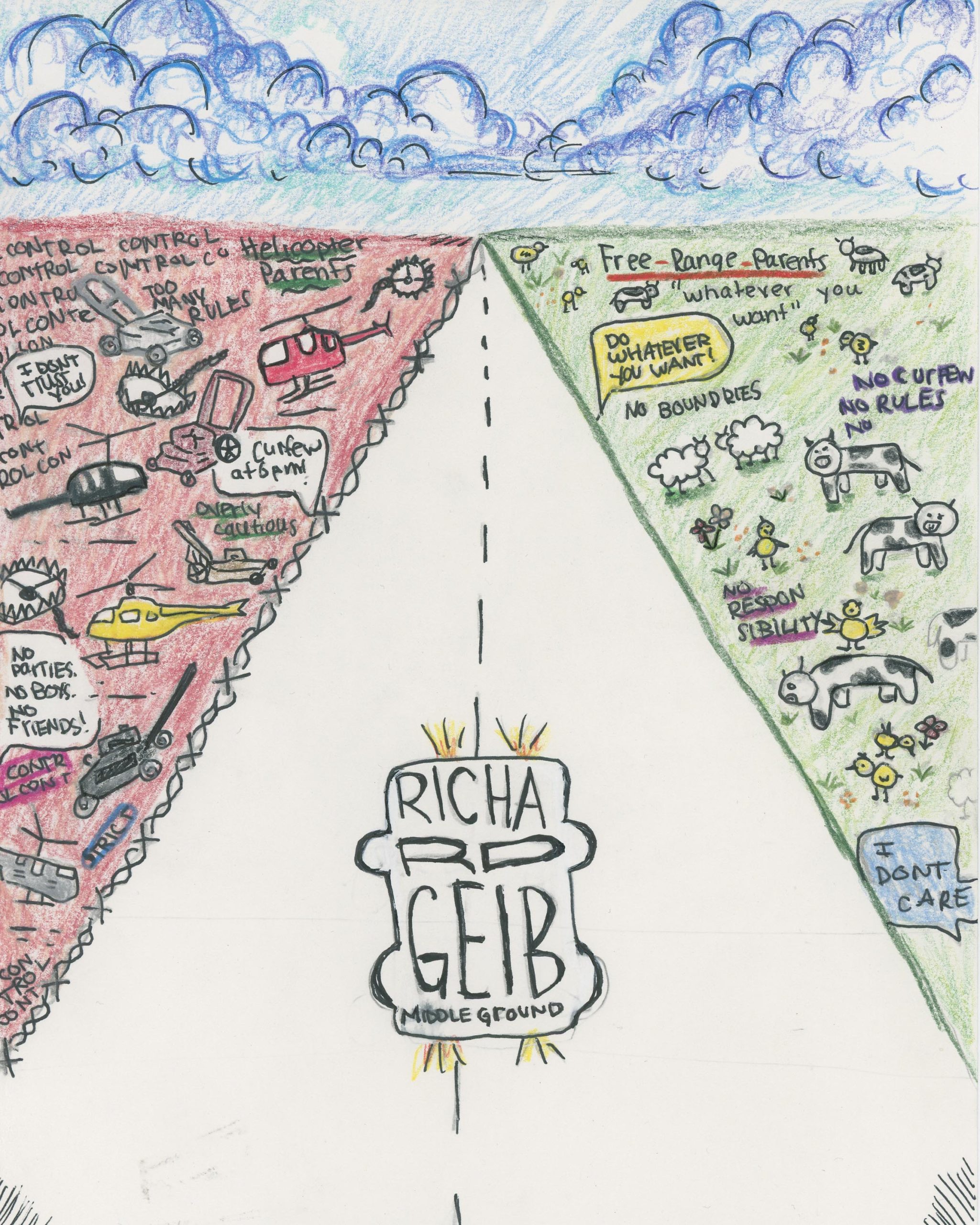

My wife is much more chary of technology in the lives of my daughters. We both felt as if the technology was a tidal wave in the lives of our daughters, and we struggled to try and control access to it. We wanted them to have a healthy relationship with it. But it is not easy. In elementary school we had strict iOS Screen Time controls on her iPhone, no access to the World Wide Web, and the phones shutting down from bedtime until school time; I didn’t even allow them to have an iPhone and access to the Internet until sixth grade. My younger daughter chafed against these restrictions in elementary school, until she thanked me for them in middle school. My older daughter is a sophomore in high school, and at this point I pretty much let her do whatever she wants online. She is well launched, and I don’t worry about her technology use. (If I see a problem there, that could change.) With my younger daughter I still hold the line on technology, and we clash on limits. She is in that hive-fever state “Lord of the Flies” mindset, where young people are confronting moral dilemmas and making decisions about who they want to be – my older daughter has already made those decisions. For my younger daughter, it is a delicate and important time of life. She is vulnerable to peer pressure, and she is open to being lied to about important ideas – she lacks the perspective to call bullshit on snake-oil sold online.

But this is what I think: I cannot control TikTok or Instagram or whatever digital popular culture is out there being transmitted into the brains and consciousness of my daughters. It is beyond my control. And unlike some parents, I am uninterested in getting too much into a long-term struggle for control over technology with my daughters. “A little bit of dirt is good for a kid,” runs the aphorism, and I don’t think exposure to certain harms occasionally (misinformation, pornography, cruelty, whatever) will ruin my daughter. She is not a wilting lily which will fall to pieces at the slightest shock. Just like there are dark alleys and dangerous corners to be avoided in the real world, I would teach her about sketchy places online and how to recognize and beware of them. She has a modicum of common sense and we build on that.

Moreover, it is not all bad out there in the digital world. There are social benefits to engaging online with the world – other parents post videos of my daughter scoring goals on Instagram, and her friends are all there interacting; it is important she be able to engage there. Much of a young person’s social life takes place online, I came to realize, for better and for worse. Banning my daughter from social media would have a real opportunity cost in terms of all the group interaction taking place there which she would miss. I have been forced to conclude that, observed too strictly, my “KILL YOUR TV!” mantra is parental malpractice in the age of the iPhone and social media for my kids, and so I have made adjustments.

This is the digital world they live in. It is not going away. My daughters will have to make their way in it. I cannot control, or even know about, the vast majority of what is there. This is the world we adults have created, for better and for worse, and we might as well do our best to help teenagers live in it. The technology is powerful, no doubt.

But as a parent I am powerful, too. That is where I have leverage. My daughter lives with me. She looks to me for help to make sense of a complicated world, or at least she does now. Soon enough she will push me away and rebel while struggling amidst the disorienting fumes of hormone-soaked adolescence, but we are not there yet. I must use my time now.

So what does this mean in real life?

Well, I will tell you.

First of all, at the beginning of sixth grade I read “Lord of the Flies” with her. It is the ultimate middle school book, in my opinion, and I have had numerous opportunities to discuss the lessons of that novel and compare it to her experiences with group-think, peer bullying, animal aggression, and decision-making in middle school. “Are they acting like Jack or Ralph?” I ask her when she tells me a story about “drama” which takes place at school, and there seems to be a lot of drama there. I try to be a constant presence in her life – in good days and bad – which earns some respect from her in terms of our family values and how one should act.

Let me explain further. My 13-year old daughter plays soccer and practices boxing. Being part of a soccer team is hugely educational, and often I am reiterating the idea of discipline and doing your best in the face of adversity. “Just do your best and nobody else can ask more of you,” I urged her yesterday, when in tears she told me she could not run three miles with the rest of the team. “Confront your fears and FIGHT – COURAGE!” has been my consistent message. I try to be consistent. My daughter, again in tears, also pleaded to stay home from school Monday morning. “I don’t feel well!” I made her go to school. “We go to school, even if we feel a bit under the weather, unless you truly are sick,” I told her. “Suck it up, buttercup.” So many of my failing students are always missing class for one reason or another, and I want my daughter traveling a different path than that. I try to be consistent with my expectations, and my daughter went to school and did fine. She is learning. There are high expectations, adapting to circumstances, and moving past obstacles.

Boxing lessons over the past year have also opened up doors for learning. During our travels to weekend soccer tournaments she has all over southern California, my daughter and I have had the opportunity to watch all the Rocky and Creed boxing movies; they have been instructional, as well as educational. “You are crying about having to run three miles in practice today,” I asked her, “when we were watching Adonis Creed run up mountain roads while carrying weighted vests, or towing an airplane with his leg power.” This is what elite athletes do. “Why are you crying?” My daughter begins to see what real athletic training looks like, and she will grow in her ability to train hard. Or at least I hope she does. My wife and I will drive her back and from practices, and pay for the coaching and competitions. She sees me compete in tennis leagues and knows how seriously I take the endeavor. I am not asking her to do anything I would not do myself.

My daughter and I have also had many conversations about fights and fighting. Her middle school has a rough crowd of kids who seem to get into fights often, for seemingly no better reason than they are bored and looking for action. “Stay away from them,” I warn my daughter. “There is nothing to be gained from getting into it with those trashy kids.” But she is a boxer, reputedly, and her friends know that; they seem to put my daughter forward as some sort of guardian against bullies. “What if I cannot avoid a fight, daddy? Can I defend myself?” she asks. “Of course. But 99% of the time you can avoid a fight. Stay away from trouble! Give those rough girls a wide berth. I don’t want you fighting!” I hold firm. A few weeks ago she told me one of her friends (a bit of a trouble-seeker herself) had set up a fight after school with another girl, and my daughter felt beholden to back her friend up. “No, no, no, no! She is looking for trouble, daughter mine. The fight is not necessary, and you are allowing yourself to get dragged into it!” I told her emphatically. I could see the strong peer pressure that made her feel as if she had to stand up with her friends in the face of enemies. But I told her to avoid the whole thing. There ended up being no fight. But at this incident recedes into the past, I hope the lessons stick. I hope she learns.

She is 13-years old. I try to watch out for my daughter without trying to control her every action; I would teach her, if I can, so she can make her own smart choices. I would hope eventually to parent myself out of the need to parent, with my daughter able to take care of her own business.

And the example I set for her in how I interact with people and conflict is so important; how I teach her in how I live – how we live – without having to use words. This is huge.

“I spent thousands of hours and years of my life learning how to fight, daughter mine,” I tell her, “but I have not been in a fight outside of work since I was like 14-years old. Elizabeth, can you imagine me getting into a fistfight and rolling around on the ground wrestling with some grown man in a parking lot or wherever, with you and your mother watching with embarrassment and alarm?” It could happen. But it is hard to imagine it. My daughter knows that. Because she has seen it with her own eyes in our family life. A dad on her soccer team recently got into some fight with a bumptious panhandler and broke his hand (“boxer’s fracture”), and another dad came to me and asked, “Really? A fistfight? What is he? Like 15-years old?” I totally agree.

Sure, there are times when a person has to fight. And certain places and people see much more fighting than others. But almost always a person can avoid a fight through prudent caution, situational awareness, and good judgment.

So much of life is just showing up. As a father you make yourself a daily presence in the lives of your children. They see how you live; they bounce ideas off you. Together you can discuss almost anything, and find a way forward. But you can only parent if you are present on a daily basis in the lives of your children. And as a parent you have to do most of it before a young child turns 15-years of age and suddenly thinks everything you say is suspect or silly. I always love this quote by Mark Twain:

“When I was 17, my father was so stupid, I didn’t want to be seen with him in public. When I was 24, I was amazed at how much the old man had learned in just 7 years.”

How about this reality: some 8.4 million children in the United States, 1 in 4, live without a biological, step, or adoptive father in the home. That is about the saddest single fact about contemporary America, and is directly or indirectly responsible for a large share of our social dysfunction, in my opinion. Or that some 40% of babies in our country are born to single mothers?

At any rate, I have given up trying to control what my daughters see online. The use of technology by our youth culture is beyond me at almost 56-years old. So much of it is, I strongly suspect, unworthy of my adult attention. But my wife and I can control how we live in our house, however, and our daughters see the lessons in terms of how to treat people and how to be the best possible versions of themselves they can be.

Maybe the most important idea is that I do not hound my daughters about their grades. They report cards are almost always all “A’s” students with a “B” sprinkled in here and there. I make sure they put forth their best effort in school, but I don’t sweat the grades too much. (And my wife and I are both teachers!) This is what I tell them: If I see you are trying your hardest in a class, I am fine with you getting a B in it. The amount you try and how much you learn are the important parts, not necessarily the grade. I would rather you take a hard class and get a “B” than take an easier one and get an “A” (“We learn not for school but for life”).

In fact, I spoke these exact words to my daughter last night. We were on her bed reading before sleep, as we often do. We were reading “What Looks Like Bravery: An Epic Journey Through Loss to Love,” by Laurel Braitman, because I read that part of the story takes place at my daughter’s current middle school. So I bought the novel and added it to our list of books to read. The story revolves around the relationship of the author and her father who gets cancer and dies. My daughter and I have many of our best talks at that time, and our conversation strayed from the book and she asked me:

“Daddy, what if I study really hard and get a ‘D’ or an ‘F’ in a class?”

“Well, in that case I might have to go talk to the teacher and see what is going on. That would be really weird.” I answered.

I continued on and asked her, “In any case, what does a ‘D’ on a report mean in our family?”

“A ‘D’ stands for ‘Don’t come home,’” she smiled. This is an inside-joke in our family.

“And what does an ‘F’ stand for?” I continued.

“Find another family,” she answered per the script.

We laughed together.

“Good night, my darling. Sleep well.”

I learned from my own father how the steel gauntlet of parental discipline and control should be cushioned by the velvet glove of concern, patience, and compassion. The steel links which tie child to parent are forged in love, even as they are tested in the fire of conflict while growing up and rebelling against parents. But those bonds between daddy and daughter matter, in a way that the bonds over TikTok or YouTube don’t. But you can only forge those bonds by being an involved, attentive dad – but without being an overinvolved, overwhelming one.

Kids have to find their own way. The Internet and social media will be part of their journey. You do them no favors by protecting them too much from the world. So I don’t sweat the online stuff so much. “Don’t prepare the road for the child, prepare the child for the road.”

So I guess YouTube didn’t kill me after all?

And more importantly, growing up with YouTube and TikTok didn’t kill my daughters.

Because social media and ubiquitous technology are powerful influences on a young person and their childhood, no doubt.

But so are their parents, too.

My daughters travel through their lives protected and empowered by a father’s steady patient love. My hope is that this helps foster in them the CONFIDENCE and COURAGE to GO FOR IT – to nourish ambition, embrace opportunity, live joyously, and enjoy success.

That is my hope. I can only do my best.

The rest is up to my daughters.

Dear reader, I don’t want you to think I am firmly in control of the parenting gig. I don’t have it figured out. Far from it. Who knows what will come at me next? What new development I did not see coming? What crisis(es) will take place? Parents, worry – that is what they do. “He that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune,” Sir Francis Bacon claimed, and I think of that not infrequently. You do the best you can as a parent, and then you back off and let your children live their own lives. The whole project is shot through with uncertainty and risk. You worry.

But I am quietly confident. My daughters are not fools. They have developed positive traits of mind and workable tools which will help them. It will work out. They will have the good sense to ride the waves of success and joy in their adult lives and resilient enough to survive the troughs of disappointment and misfortune. They are close to being well-launched. I have faith.

We shall see.

ChatGBT AI Bot Advice to Me Today: