I am 54-years old.

I have been a teacher for 27 years, exactly half of my life.

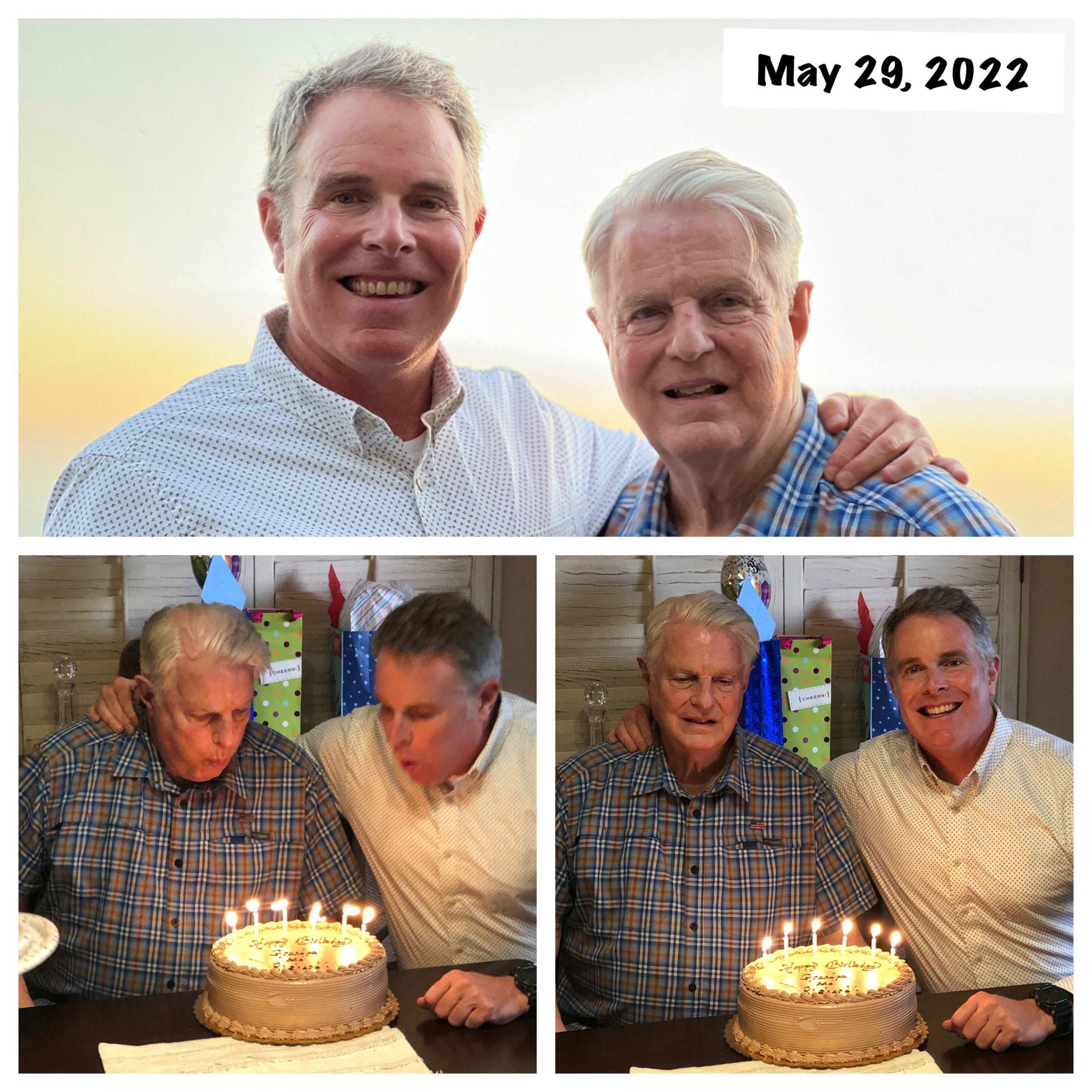

I went to school and then college. I got a job and worked. Got married and raised a family.

Does my adult life consist mainly of sustaining myself and my wife, helping to pay our bills, and raising our two daughters?

Much of it does.

Do I like my job?

Well, much of my job as a writing and history teacher coincides with my personal interests. I have a passion for what I teach, and so it is fair to say that I have a vocation. That might mean I don’t just have a “job,” I have a career — a calling. I don’t work merely for money. I enjoy the subject matter I teach, and I get paid for it. Often I find my work fascinating.

That is important to me.

But I don’t enjoy all aspects of my job.

Who does?

But do I enjoy enough of them to keep doing the job? After 27 years do I still enjoy it?

Do I have a choice?

We work until we are old enough to retire. Any time after that in old age is a bonus.

Then death.

Many (most?) Americans work until they die. They can’t afford to stop working.

School. Work. Death.

It is a depressing vision of life, looked at from that angle.

And it is nice to argue that we should all discover our “passion” and find a way to make money off it. That was what exercise physiologist Leon Skeie, father of fellow graduating senior Stacey Skeie Rees, the speaker at my Corona Del Mar High School graduation in 1985, advised us to do. It was not bad advice. Take the time to identify what is your vocation in life, and then relentlessly pursue self-actualization in the workplace. That is the road to happiness, Skeie suggested.

But that’s not usually what happens. Most Americans simply get a job after school ends, and they slug through it for the paycheck. Most don’t have much of an opinion about whether they like their job or not. It is their job. They just do it. Fun is what they do outside of work. If work was “fun,” we wouldn’t call it “work” — or so the argument goes. We do it to get paid, not to derive pleasure.

Is that what happened to you, Richard?

So the same question again: Do you derive satisfaction from teaching? Do you find what you do to be meaningful and important?

Yes, I do.

I am luckier than most, I suspect.

But after 27 years?

I still feel as if I want to do the best possible job I can for my students. But as for my superiors in the public education system… I feel something very different.

How about the case of a former student of mine who chose to attend West Point Military Academy after high school and later served as an officer in the US Army. Did he get what he wanted? I can understand wanting to follow in the footsteps of famous military men like Ulysses S. Grant, Douglas MacArthur, Dwight Eisenhower, and H. Norman Schwarzkopf. I get that. But to actually work in the army on a day-to-day basis — the bureaucratic reality of a litany of mindless rules to follow and paperwork to be filled out, as well as the petty personal rivalries of army officers on a day-to-day basis? Well, that is quite a different thing than “honor, duty, and country.” You might be attracted to the higher call of serving your country as a soldier, but living with the indignities of actually being in the army is a different deal.

I spoke earlier this week with a local deputy district attorney. He had worked as a prosecutor in the “justice system” for almost as long as I had been a teacher. I asked him if after so much time he still believed in what happened in the law courts? He was not so sure. Maybe? Sometimes? “We do the best we can” I wanted him to elaborate. I asked questions: “Do victims of crime really get ‘justice’? Are the accused always ‘guilty’? How do you balance the rights of the accused versus the rights of the abused? After so many years do you still feel good about what you do?” He replied, “Well, it’s complicated. Usually we succeed. Usually I do.” This is something very short of a ringing endorsement. In the most murky, complicated cases “justice” can seem to be a most elusive, slippery goal to realize.

There is the theory. Then there is the reality.

How about my case as a teacher in the California public schools? Do I believe in the American public education system? The reality of public schools as they are? Well, it depends. “It’s complicated.” In some areas the service provided is excellent; in other areas it is execrable. The problems are almost too many to count. The assistant superintendents, elected school boards, liberal “identity” politics, special education law, the teachers’ unions, and teacher education programs in universities — they all bear much blame. How about the Western Association of Schools and College, the National Council of Teachers of English, or the National Education Association? Do I believe in them? Nope. After long acquaintance, my faith in them grows less and less each year. If members of those organizations were around, I would walk across the street to be on the other side; if they advise me to vote one way, I would be inclined to vote the opposite: this is where experience has led me. The public education establishment is almost the enemy — that is the emotional place where I have arrived at over time. The uneven school system in America will not improve — that much is clear to me after twenty-seven years. I feel increasingly alienated; I am behind enemy lines.

So am I going to break with the entire public school system and call for it to be razed to the ground, as did award-winning New York public schoolteacher John Taylor Gatto? Quit my job in protest and write a poison pen letter to the newspaper explaining why?

No.

I will do the best I can, despite everything. I will continue to do so until I retire. I will believe in what my students can do, with any help I can give them. I still want to do the best job I can for the students in front of me. That much has not changed since I started teaching in 1993. But I don’t believe much in the apparatus I serve in, which has major (irreparable?) quality control issues, to put it mildly.

There is the theory of being a teacher. Then there is the reality of working as a teacher in a real school. A veteran teacher will know the difference.

Is it different in any other profession?

The practice of medicine, for example?

There is the theory of being a doctor and healing the sick. Then there is the reality of a physician who works as an employee of a specific health care system. One might aspire to the theory but become disillusioned by the reality. In fact, that probably happens most of the time. I would be surprised if it were otherwise.

But at least those who are disappointed by aspects of their profession, like doctors or teachers, have a “profession” to complain about.

Those who populate the “working class” often have few illusions that their jobs would offer any satisfaction other than the paycheck — or that “work” is anything other than work. As workers claim in socialist countries, “We pretend to work and they pretend to pay us.” But in the USA they can usually fire employees who grow complacent in their work. The lowest paid employees with the least education are the ones most at risk of being disrespected and replaced by their employers.

Members of the “working class” are born. They leave infancy and start school, then enter the workforce and labor, and continue to labor until they die. Unless they transcend the economic class of their birth, they often work for low-pay in disposable jobs they dislike, over thousands of hours every year — an employment history which, when all added up, combines to form a huge, unhappy chunk of their lives. If the most valuable commodity in life is your time and energy, you don’t want to waste vast stretches of your time and energy doing something you don’t want to do.

At least I never had to do that.

But I do have to pay my bills, the same as anyone else. Provide for my housing and buy food for my family. Raise my daughters and pay my taxes. Make car payments and buy car fuel and pay auto insurance premiums. Take care of any medical bills. Cover the unexpected costs which always arise. It all adds up. Adult life: it is no small labor.

Many of my friends are so exhausted after thirty or so years in the workforce they just want out. One friend told me he wants to sell everything and move to the desert where he can quietly and cheaply live out his days. He wants peace.

It is much the same for many of my friends. Their kids are almost raised. They approach retirement. They want something different. It has been a long time.

I don’t blame them.

Others of my friends seem to like work. They usually own their own businesses, and they have easier and more pleasant work situations, even if they have the heavy burden of responsibility and being in charge. They seem to be able to work indefinitely.

And then there are the laboring poor, who are barely hanging on. They work but still have little money. They despair. They will never be able to retire. They will struggle until they die. Death is almost a release from the struggle.

Then there are those who don’t ever seem to work at all, for whatever reason. They have even less money, I suppose. God knows how they get by.

In one’s youth there seems much to prove to the world. To do something memorable, leave your mark, become justifiably famous, and change the world. There is ambition. An embrace of the possible. The desire for a big life.

I don’t want a big life. Not anymore.

I find the concept flawed.

I want peace.