Some Meditations on Reading a Long Book During Quarantine in 2021: Patience and Perseverance, Purpose and Fulfilment

They say that a book should be only as long as it takes to tell the story. It should be neither longer nor shorter than that.

But that is plenty vague, and leaves lots of room for different lengths of books!

I think about this as I am half-way through David Copperfield. I have read every page carefully and am on chapter 30. I have been reading the books assiduously for over two weeks, and I am only halfway done.

I am tired. This is a long book!

The narrative is lengthy. This happens and then that. Another thing happens. Then another and another. It goes on and on. I grow weary.

Don’t get me wrong: I am enjoying David Copperfield. There are many indelible scenes already: The pupil “Master Copperfield” showing up to boarding school and seeing the sign “Take care of him. He bites.” — and looks around for the dog it refers to and then realizes the sign is for him to wear. David desperately running away from the Murdstones and walking hungrily for several days with blisters on his feet to his aunt’s — his terrible Aunt Betsy, whose defects of shortness of temper and rude bluntness turn out to be more than balanced out by loyalty to kin and generosity to David. You think her a disagreeable crank at first but come to see her in a more complicated and better light over time. It reminds me how our vices are so often interwoven with our virtues; you cannot separate the one from the other.

This is good stuff.

It is a mark of high-quality literature that the characters and actions in the story stay with you over time. Will I ever forget the baroque and ruined Miss Havisham, jilted at the altar, and her adopted daughter Estelle and revenge against the male sex? Pip terrorized by the escaped convict at the beginning? Sidney Carton and his dissipated lifestyle in A Tale of Two Cities, and his unforgettable redemption at the end? The first few lines of David Copperfield or A Tale of Two Cities are famous almost to the point of caricature.

That is the reason I made one of my goals in 2020 to read the other major works of Charles Dickens.

But David Copperfield is such an exhausting, overwhelming marathon that I think I might take a break afterwards.

During my senior year of college in an honors Russian literature class I read Tolstoy’s War and Peace in two weeks, and immediately afterwards Anna Karenina in one week. I remember enjoying those stout novels, and any pains of fatigue from their reading have not survived in my memory since that time over 30 years ago. As for Charles Dickens, I read A Tale of Two Cities for pleasure one summer in college, and Great Expectations a year or two after graduating. I don’t remember being bogged down by either.

But I am still exhausted a year after reading Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. What a long and wrenching tale of several lives in partially intersecting plot lines! An exhausting trek all over France in times peaceful and revolutionary. A journey so long you feel as if you made it yourself by the end. I don’t argue Les Miserables was a journey unworthy of being made, mind you, but it was a journey not easily or quickly completed. It was a four or five-course literary meal. Les Miserables was an adventure I’ll never forget, but It was both rewarding and draining — and I am not sure which was the predominant. Could Hugo have used an editor to slim it down? Cut out tangents without hurting the main storyline? Use fewer pages to describe the Parisian sewers? The unabridged Les Miserables audiobook comes in at just under 68 hours in duration. Is this too long?

Or am I just older and have less intellectual stamina to read than when I was in my twenties? Over time have I remembered the joys of those books but forgotten the hard-work in reading them for the first time? Or maybe, like in Les Miserables, is David Copperfield really that long and involving of a story?

Part of the problem is that Charles Dickens wrote his novels in serial format where chapters were published piecemeal in magazines. This encourages a writer to go on at length, as he is paid by the word. And readers digest narrative little-by-little over longer stretches of time, and so the author need not worry as much about overwhelming the audience by pursuing semi-relevant tangents with an army of supporting characters

I, on the other hand, am reading David Copperfield uninterrupted in one complete book. In the middle of it, I am almost overwhelmed. Bogged down. Words and words and more words.

Or maybe I am just grown lazy and inattentive. The smartphone virus has caught me, too, and I might have a smaller attention span than did readers in the past. Maybe that is it. Reading novels is perhaps gone out of fashion, and reading long and old ones even more so. We prefer to watch something, not to read something.

Most people I know seem entirely capable of sitting down and watching fully 60 or 70 hours of Breaking Bad or The Sopranos miniseries on Netflix without too much difficulty.

But they aren’t going to sit down and read David Copperfield or something similar.

What is it about our modern minds which makes sustained attention to the written word difficult?

The audience at the Lincoln Douglass debates in 1858 listened patiently for three hours as speakers debated at length the burning issues of the day dealing with the extension of slavery into territories acquired in the Mexican War. From all reports audiences followed and enjoyed the intellectual repartee of the debates. This was their entertainment. It was text-based. It took patience and labor to comprehend.

Our digital era wants 4-5 minute recaps of news highlights on YouTube and a few sentences of a social media post. You demand more than that and your audience clicks away to somewhere else. We have collectively the attention span of a gnat.

Perhaps we have more media choices, and so our media viewing is by degree more diffuse and desultory. We are like hummingbirds that fly from digital place to place in search of something more diverting. Our brain leads our eyeballs to search for another digital hit of dopamine in the ever-moving matrix of pixels on the screen. Titillation and distraction are our national narcotic. We avoid difficult and important business by picking up our smartphones and escaping into the ease of the electronic ether. It is always available. It promises relief for boredom and unease.

It used to be different. Before electricity it grew dark at night and one read a bit or maybe wrote a letter and went to sleep. The written word on paper was pretty much all you had. So you returned to it, and you muddled your way through.

This muddling through has happened often with me during the government lockdowns. In Allan Cumming’s book Not My Father’s Son, for example, there were passages so emotionally painful to read that I put the book down. “I am not up for reading this wrenching account of an angry son screaming at his elderly father,” I thought to myself. Ugly accounts of ugly family secrets being unearthed. “I don’t have the energy for this right now,” I told myself.

But ten minutes later I took up the book again and waded through Cumming’s filial pain and anger. There was nothing else to do during quarantine. So I might as well keep marching through this unpleasant part of the book until it gets better. It almost always does. Patience and persistence.

Maybe if I had had more options in a non-quarantine time, I might not have returned to Cumming’s book. But I didn’t have more options and so I returned. In this way I read some fifty books during the Coronavirus months of 2020. Some of them were short easy-reads, but many of them were not.

There are 24 hours in a day, and you can get a lot done if you don’t waste time — if you don’t allow yourself to be distracted.

We live in a mostly post-text world of digital images, online videos, and social media posts where there is always something new (something “viral”!) to view on the smartphones which always seem to be in our hands. So distraction and diversion have never been more ubiquitous than today.

And so our sustained reading, and therefore our sustained ability to think on a single subject at length, suffers.

I too have a smartphone and use it. But how exactly am I using it? Towards what end?

That is an excellent question to ask oneself. I must remember to control my media intake in a conscious manner. Are you using the technology, Richard? Or is the technology using you?

So you must resolve to do the following: Stay the course and finish David Copperfield. Continue to write on almost a daily basis. Drink deeply from those springs which give you enrichment and fulfillment. Keep on in this way indefinitely.

Use your time, Richard. Develop any talents you might have. Seek to maximize your potential. Take the best the 21st century has to offer and leave the rest.

Commune with Dickens and Schubert and all the rest. Look inward and find peace.

If peace is not easy to find in 2021, it is not more difficult than it was in 1850.*

We change in technology and the organization of society, but we don’t change in our need to live a life of meaning in connection with others.

We change, but we don’t change.

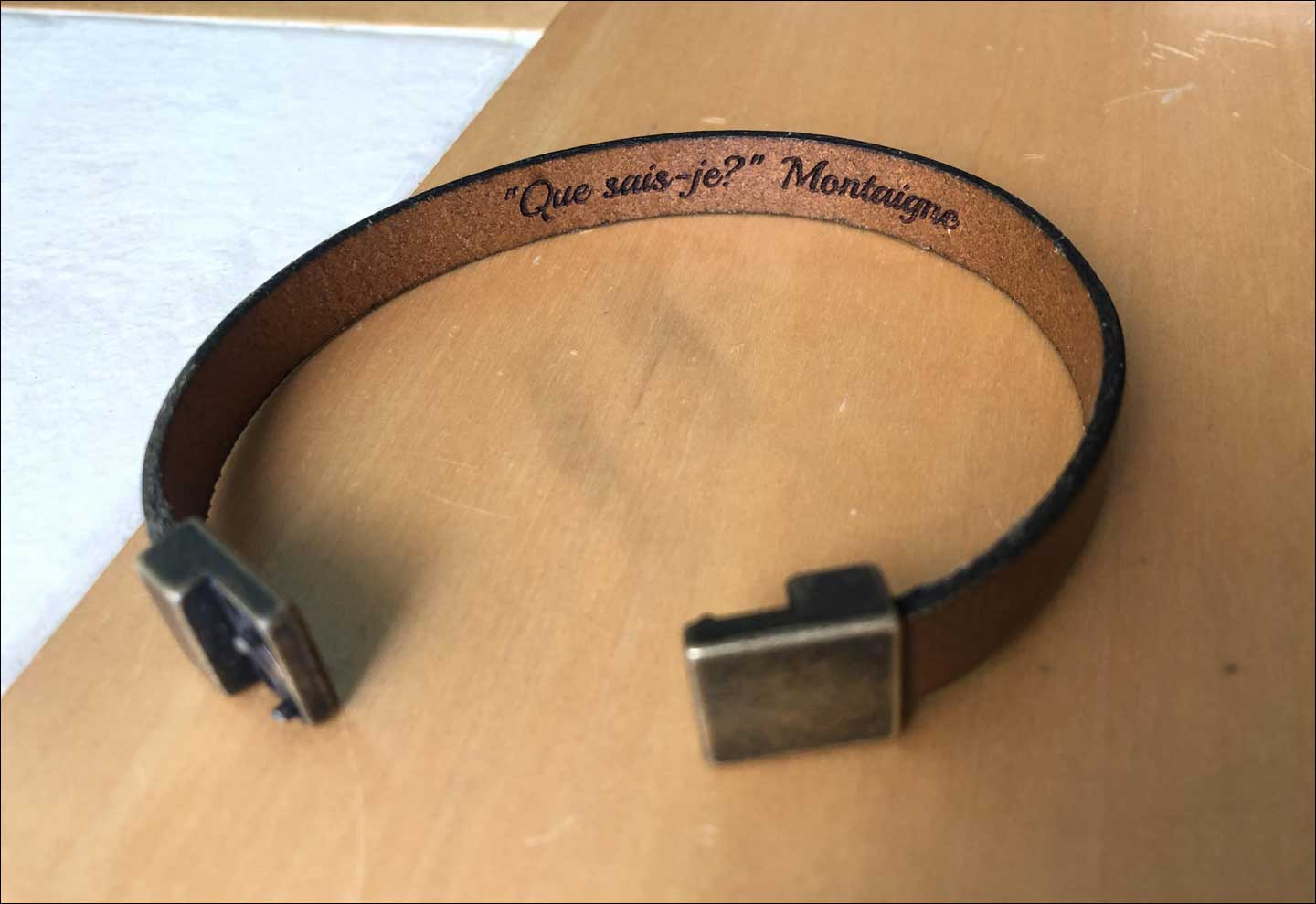

So, Richard, “essaie” to live like your role model Michel de Montaigne — Que sais je?

Is this not “meaning” and “connection”?

Yes.

Happiness even?

No, not “happiness.”

I place no faith in that term and don’t seek it. Happiness is too transient. Too dependent on the vagaries of fate. Not durable enough.

Rather, I seek purpose and fulfillment. And usually I find them. They are the all-weather gear which lasts. Fulfillment might be hard-earned, but it does not forsake you. Purpose is the fuel which powers a person to fulfillment — and maybe even to happiness, if they are lucky.

Purpose gives your life direction. It gives your life a point. “No wind favors him who has no destined port,” Montaigne reminds us.

To read and think deeply. To be open to new experiences and new people. To never stop learning — to remain always a pupil. To live life consciously and deliberately.

Knowing it will be over soon enough.

Amen.

* 1850 was when David Copperfield was published.

An Engraved Men’s Leather Bracelet