“Men have become the tools of their tools… Most of the luxuries and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind.”

Henry David Thoreau

Last week I wrote at length about my long slog through the Charles Dickens novel David Copperfield. I wondered why our society seems to have moved away from text and novels, and gone in pursuit of bite-seized social media posts and “viral” online videos.

And I thought about how a friend recently told me that the popular Breaking Bad series on Netflix, watched by millions and millions, was one of the best TV shows ever produced.

His comment got me thinking. Was an artistic production like Breaking Bad simply the contemporary version of David Copperfield? A similar entertainment offering in a different time and media environment? How are the two similar? Dissimilar?

Well, there are plenty of similarities. How do I know this? Because after reflecting on David Copperfield, I decided to watch the entire Breaking Bad series and compare them. I subscribed to Netflix for one month, and I dived into the deep waters of Breaking Bad at the same time I was reading David Copperfield. Five days later I am almost done with the second season of Breaking Bad. I have watched some 13 hours of the TV show so far.

First of all, both are lengthy productions. Breaking Bad clocks in at some 60 hours of viewing over six seasons. It will take awhile to get through the story of Walter White, the feckless high school chemistry teacher turned ruthless drug kingpin. Similarly, the audiobook of David Copperfield takes 29 hours to complete. Moreover, both are complex stories which track protagonists through the twists and turns of their lives; this is why they talk so long to get through. The characters are lively and interesting; the writing is sharp and insightful in both stories. There are major and minor characters. Breaking Bad and David Copperfield were both designed to be delivered to the audience piecemeal in installments for a paying public. Both narratives can hold an audience and entertain it, and both were successful commercial enterprises. But there are slight but important differences which tell us a lot about the different cultural moments which produced them — to be more specific: one is video, and the other is a book. The difference between video and text, and what it tells about our society, is the point of this essay.

I have continued to read David Copperfield since my last posting. I am currently on chapter 48. There are 64 chapters in the long book, and so I have some 15.5 chapters left. I will finish soon. It will have taken me almost a month to read David Copperfield. A bit more and then I will also finish Breaking Bad.

How do you read a book almost 800 pages long? How do you undertake to watch an entire TV series? Like any long journey: one step at a time. Patience and perseverance. Similarly to how they tell you to eat an elephant: one bite at a time. Little by little you make your way through.

For all their similarities in length, there are key differences I can already descry. First of all, Breaking Bad is easier to watch than David Cpperfield is to read because the one is a video and the other is a novel. Not that Breaking Bad is easy, necessarily. For example, I find it painful to watch Walter White’s marriage fall apart, in the same way it is painful in real life. There is also graphically violent scenes which are unpleasant to view — a man’s murdered corpse is cut up, mostly dissolved in acid, and then the viscera which remains are flushed down the toilet. Yikes! But the visual images allow for a person to sit back and mostly watch. Breaking Bad does require patience to make it through six seasons, but there is an element of passivity to watch a show like Breaking Bad on a screen which is different than decoding text like David Copperfield which requires a more active effort.

This is important, I think.

I remember a young adult I met several years ago. She told me that her primary pastime outside of school was to watch full-length movies and multi-season shows (like Breaking Bad) on Netflix. I think her not unusual. Many Americans enjoy sitting back and streaming hour after hour of multimedia content. It is a multimedia smorgasbord; there is almost no end to the videos one can stream and watch online. Sit back, click on the link, and escape into the movie. This is popular.

Or one could also go online to read The Odyssey, the King James Bible, The Call of the Wild, or The Great Gatsby. And do so for free — no need to pay for a Netflix subscription to read books in the public domain. But doing that is not so popular.

I think this is, in large part, because it is harder. And the reward is slower and more subtle.

That young lady who loved watching Netflix late into the evening? She claimed she spent much of her summer doing so.

Well, she was not so great at reading books and writing essays during the school year. She was not terribly enthusiastic about reading or writing at all.

She was more a video person. Not really a text person.

She is a great representative of our cultural moment.

We live, more or less, in a post-text age, it seems to me.

Most young people read books only when assigned them in school. They go to books when forced to by teachers who assign reading. So reading becomes a chore, not a pleasure. As a result it is not done often, and so it does not come easily. In contrast, Netflix and Disney+ and YouTube have never been so popular, and sophisticated videogames are maybe even more so.

We love to watch the pixels dance upon the screen; it seems we become hypnotized by the dazzling stream of images our eyes drink in. The brain comes to crave more and more visual stimulation. “Industrial societies turn their citizens into image-junkies; it is the most irresistible form of mental pollution,” Susan Sontag observed way back in 1977. In such a world drowning in imagery on screens reading text in books is slow and comparatively boring.

Does that reality explain a lot about us? Our cultural moment? Our media-saturated society?

Does it explain the popularity of conservative talk-show TV, social media, and meme-based politics in America? The rise of disinformation and conspiracy theories on the political right? What else could explain the QAnon phenomenon? How could people capable of tying their shoes fall for such outlandish falsehoods spread online? Does a “closed epistemic system” online explain the Manichean “cancel culture” on the political left where Wokescolds seem unamenable to complex dialectic and nuanced narrative? Are simplistic right-versus-wrong political multimedia messages a result of our diminished ability to understand complexity? A black-and-white self-righteous simplification of the world, instead of looking humbly into the nearly infinite shades of gray? The victory of the simple over the complex? The image over the word? The meme as a cultural metaphor for our troubled time?

The strident and the extreme on social media receive so much more attention than they deserve. The attention the loud and the shameless get in the current entertainment/information economy is undeniable: the spectacle sells, it garners our attention. The outrageous online they take up all the oxygen in the room. To be ignored is the unpardonable sin in today’s media ecosystem. Being shameless can be an advantage.

Is not Donald Trump and his Twitter account and his rallies, and his enemies and their Twitter accounts and their protests, the very proof of this? Of our coarsened democracy? A reality-TV celebrity as president? Evidence of our diminished ability to think and communicate? People yelling at, rather than talking to, each other? An inability to agree to disagree? Politics as a zero-sum game? Like combat, or a raging prairie fire? The endless “culture wars,” and desire to vanquish the other? Should social-media be more aptly called “anti-social media,” in practice?

Is this a devolution? A step backwards instead of forwards? Not an enlightenment, but a dark age? Instead of a place of cultural confidence, a place of anxious backlash? Intolerance, irritability, and instability? Do we rely therefore on simple stories as a crutch to keep away the chaos and the darkness? Do we demand less, but promise more? Are we coming to resemble those pre-print cultures which relied on graven images to instruct? Are we moving back to a world before the Gutenberg Press where the Catholic faith used idols in churches to teach basic theology to a semi-literate population? Or moving towards the dystopian worlds of 1984, Brave New World, and Fahrenheit 451 which embraced screens and technology but actively abjured books and complexity? Or the world as portrayed in the movie Idiocracy?

This, I think, is the legacy of our 21st century multimedia world: we have become less mature and adult, and more childlike and simple. Our ability to think is lessened. Our patience is less. Our communication is stunted and too often unsuccessful. We talk in 246-character bursts. Too often we think like that, too.

We are overwhelmed by information. We are too often bereft of wisdom. T.S. Eliot wrote, “Where is the Life we have lost in living? / Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? / Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” Eliot wrote that back in 1934. What would he think now in 2021? How about by 2051?

I enjoyed Breaking Bad, as I enjoyed David Copperfield. But I wonder if the YouTube/Twitter/Netflix/Instagram online ecosystem we have built is feeding our impatience and distraction — making the world easier than it should be. Is it just sitting back and watching a video, instead of sitting up and reading a book? A passive versus an active stance? The difference between Breaking Bad and David Copperfield might be slight, but it is important. As Marshall McLuhan wrote in the 1970s, “The medium is the message.” Breaking Bad, over a decade after its debut, still has great cultural cache in America. David Copperfield, in contrast, is like an artifact from an archaic world and is largely ignored. Millions watch Breaking Bad. Almost nobody reads David Copperfield.

This is a step backwards, not forwards, in my opinion.

It is frustrating for me personally. Back in 1996 when I first started my personal webpage, as a young adult, I publicly called on my fellow Americans to kill their TVs and do something more active and productive with their precious time and energy, as I reflected on here —

”Kill Your TV, Twenty Years Later”

November 13, 2015

Four months ago, as a parent, I wrote the following piece recently where I count my daughters swallowed up and devoured by the insatiable maw of modern mass media —

“Kill your TV”? I Count Myself “Killed” by YouTube

October 1, 2020

You can see how the situation progresses: the three network channels on the TV in the living room during the analogue era had morphed into a hydra of innumerable different media heads which broadcast into the smartphone in our hands and through all the devices in every room of our homes in the digital era. The situation since 1996 with regards to media saturation had not gotten better. By 2020 it had become way worse.

So it goes.

Have I become too much of a doomsayer?

I grant you there are those who watch Breaking Bad and also participate in a book club or read serious magazine articles and literary works; they can move easily in both the world of text and image, and my sister is one such. She heartily recommended the Breaking Bad series to me, as she has many books, too. But those like my sister are declining in number, I suspect. Serious literature via the written world with sustained narrative are crowded out by the distractions and diversions of the promise of our digital multimedia present and future. Take, for example, my sister’s son, my 18-year old nephew. He is whip-smart, has perfect grades, and certainly can read well when he wants to — he was recently early-admitted to prestigious Stanford University, and deservedly so. My nephew is an impressive young man, one of the elite of his generation. But even he is so busy with the smartphone in his hand that he doesn’t seem to read much for pleasure. Book reading among the young gets pushed to the back of the line by the many other digital attractions. They are easier. More accessible. Quicker. More popular.

Or maybe it is this simple: we are less able to sit quietly, to look inward introspectively, and in the silence to think about ourselves, the world, and our place in it. We grow bored in silence. We want more excitement, and the online world always offers it. We want dazzling digital graphics and the dopamine rush which comes from the promise of sensory stimulation for our brains in the dancing pixels on the screens in our hands. Seldom do we look inwards and reflect. Often do we look out and watch. It is too easy; we become spectators. The big tech companies — from Facebook to TikTok to Twitter to Instagram to Netflix to Disney+ to YouTube to Pornhub — regard us as “consumers of multimedia” and pump the digital juice our way. We consume it by the terabyte. Are we the better for it?

So text as it has been known, in the best sense, and what it represents in thought, is in decline, in my opinion— the contrast between Breaking Bad and David Copperfield seems to bear this out. Might serious reading and writing be dying in vast stretches of our population? As we move to online content and streaming video instead of printed books on paper, are we losing something important?

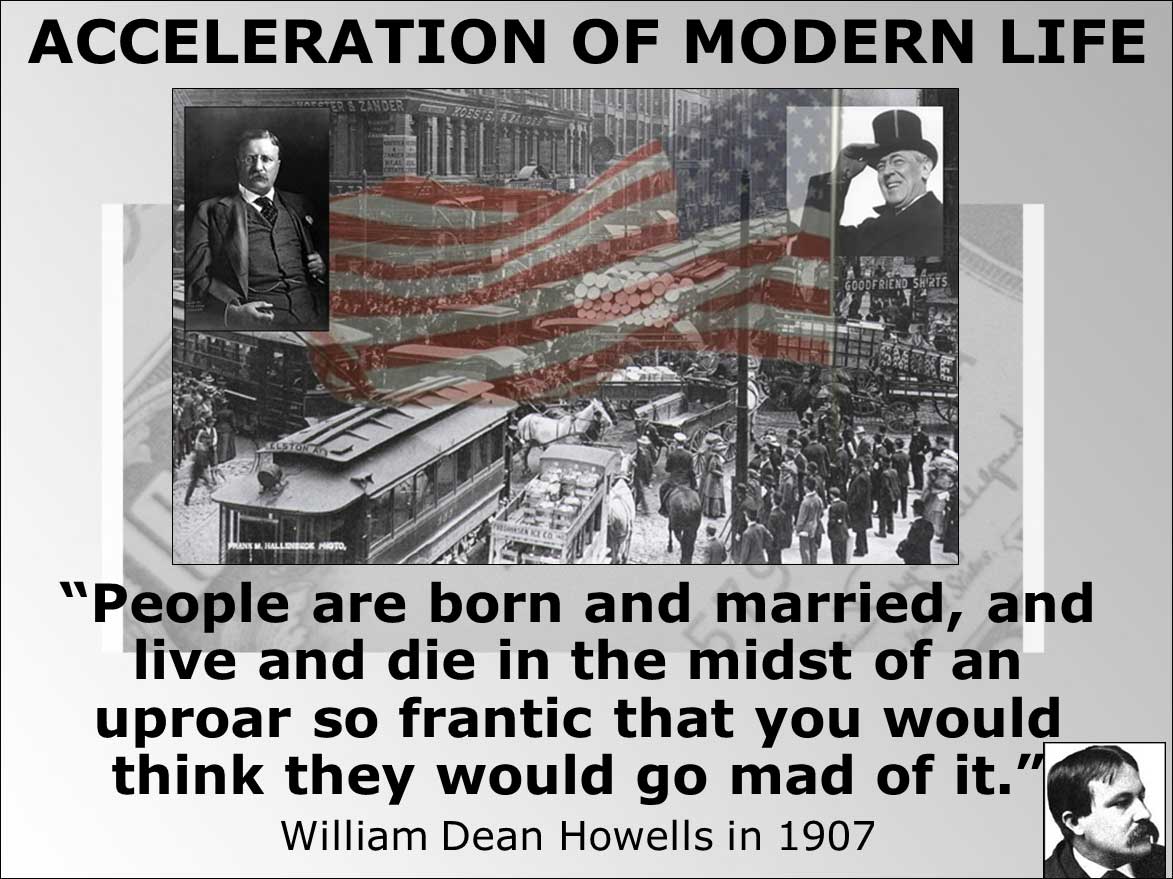

Or do people always claim it “used to be better” and the world is “going to hell”? Look at the below comment made in 1907 —

Maybe serious book readers have always been a minority, whether on the Gettysburg battlefield in 1863 or on the Coney Island beachfront in 1926 or at the Coachella Music Festival in 2009? Maybe not much has changed with the advent of the Internet after all? People from those eras managed to get through the day. Why not now, too?

Or does our brave new digital world mark a shift, as I think it does? The smartphone is so ubiquitous and revolutionary, and the Internet has changed the way we live and think in ways big and small. We are only just beginning to understand these great changes. Unmoored from the past, are we slouching towards an unhealthy future? What are the implications for us on a variety of fronts? Politics and economics? Religion and education? Art and entertainment? Loneliness and mental health? Our attachment to the past, engagement with the present, and hopes for the future?

Am I too draconian in my thinking? Do I go too far? Too much gloom-and-doom? I hope so.

But we shall see.

Let me end with the always wonderful Richard Rodriguez’s words on this matter — written back in 1999, but more relevant today than ever:

“FULL OF INFORMATION, FREE OF IDEAS”

by Richard Rodriguez

October 10, 1999

Nowadays, I find that many of the teenagers who best understand the uses of literacy are sitting in jail. Maybe it’s always been so: One needs to be in a tiny cell, reduced to writing on toilet paper, to comprehend the soul’s ache for literacy.

Otherwise: Last month, the Department of Education published the results of a nationwide assessment of student writing skills in the 4th, 8th and 12th grades. According to the report, only one in four students, in both public and private schools, can write at a level of proficiency necessary for future job success.

I don’t doubt the survey’s findings, but I am less convinced about whether writing skills are necessary for “job success.” I know graduates of some of our finest universities who are marginally literate, also highly successful college professors, bankers and CEOs.

Among the most successful executives these days–or, at least, the wealthiest–are those fat cats who are busily buying and selling each other’s communications empires. But can any of them actually communicate on paper? Just ask their secretaries!

It’s become so common, the exception would be noteworthy. We assume our politicians employ speechwriters, often teams of them. Our politicians are so busy, after all, who can expect Lincolnesque or Jeffersonian prose?

But do we ever wonder whether our politicians can write their own thoughts or, indeed, have any thoughts to write? Many politicians hire pollsters to find out what the voters are thinking. Then they tell us the results when they run for office.

Forty years ago, Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian professor of Renaissance literature, foresaw the decline of all that he loved and knew: the age of literacy. McLuhan predicted, instead, the rise of new oral/aural technologies.

In our age of Bill Gates, we like to think that we are inventing a new technology. In truth, the new technology is reinventing us–pushing us, driving our impatience, shaping our distraction. Electronic technology has exchanged reflection for spontaneity. Individual thought has been replaced by communal exchange.

The other day, I was at a fancy prep school, one of those rare schools in America where one meets young people who read. The kids were wonderful, of course, argumentative and passionate–alive. But when the headmaster was walking me back to my car, he admitted to a surprising unease. He wondered whether his school was, in fact, “miseducating” its students by making them so highly literate. “The future,” he said, “may demand minds less self-reflective.”

I think the headmaster was talking about the famous “information age” that is being advertised everywhere as our future-dot-com.

Certainly, if we are to believe the speech writers for the politicians and the CEO’s, we already are on the “information superhighway,” global and instantaneous. Along this new highway, information, not ideas, is the valued currency.

In its report on student literacy, the Department of Education found that California scored below states, like New York and Texas, comparably multiracial. Nationwide, girls were better writers than boys. Asians outperformed any other racial or ethnic groups, including whites.

The survey also found that, while students were often capable of “social chitchat” (of the sort that now is the stuff of e-mail and instant messaging), they were little able to use language for purposes of narration or argumentation.

“Whatever . . .,” American teenagers commonly say with a shrug, their anthem, when you confront them with the illogic of what they have said or when you raise a point of disagreement.

Are you ready? Kids in Bombay or in Nairobi ask the question on the TV commercial. Are you ready? The drumbeat question means to scare you into believing that you’d better get yourself on the right side of the “digital divide.”

Are you ready for a world in which everyone is talking at once but no one knows how to form a complete paragraph? Are you ready for a world in which teenagers play hate on their computers and then go out and kill their classmates at Columbine High School?

The big news last week, and the week before, was some vast telecommunications empire buying another. Today’s CEO may not know how to write, but maybe because he doesn’t self-reflect, his new corporate culture values aggression and acquisitiveness. CBS becomes MCI becomes TCI becomes GE becomes Time Warner.

The only thing that is certain is that the fat cats who sell electronic communications are becoming very rich, indeed.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the social ladder, sit the losers in prison. Lots of losers in U.S. prisons these days are teenagers. Not a few of them are layered by years of silence. Their eyes will not meet yours, much less will they offer words.

But at the place where I work, we sponsor a newspaper written for and by kids behind bars. The Beat Within, it’s called. To read it–articles and poems and stories about violence or mother or Satan or God or hope–often is to witness inarticulation transformed into the soul’s naked cry.

A girl named Jasmine: “When I find myself a victim of life’s harsher moments, I write down what I am feeling. Writing is like releasing a tear you’ve held in for years. I can do anything, feel any way, and be anybody when I write. Right now, it’s all that I have.”

Last week in Pasadena, a woman told me her brother wrote the most wonderful letters while he was in jail: “For the first time in his life, he began to explore his own evil and his goodness. And because he had no one in prison, he was willing to write to me . . .”

As she said this, I thought about a friend of mine who sent me handwritten letters, 10- or 12-page letters, from jail. The most extraordinary letters, week after week, about Russian novels, Irish poetry, the Bible and the nature of evil. It was like getting mail from the 18th century.

Now my friend is out of jail, and we exchange occasional phone calls or single-paragraph e-mail.

You will tell me, perhaps, that the bookstores are crowded (at least crowded with people having coffee). I tell you that we Americans are losing our capacity to create or understand language that is dense and structured with feeling and thought.

We may be heading for a great, global irony. Never before has the world been so quick in communication with itself. But now that we are “wired,” no one may have anything to say.

Already, you see them on the streets, adults walking or, worse, driving with their cell phones. The closer you get to their voices, the more you realize that they are merely chattering.

For myself, I find that the longer I am in correspondence by e-mail with someone, the shorter our correspondence becomes. After a time, we exchange sentences–like Post-Its.

So maybe we didn’t need the Department of Education to tell us that most of our children cannot write. American schoolchildren are, nonetheless, taller than we ever were at their age–and their teeth are straighter. They are funnier (or at least more ironic about matters like sex) than we were.

Of what news is it that they have no skill writing words of narration or persuasion? Neither do we.

One Comment

Stuart Macdonald

Great piece.

Your observations are backed by neuroscience

Check this out… our brains are physically changing…

https://academicearth.org/electives/internet-changing-your-brain/#:~:text=Basically%2C%20our%20brain%20is%20learning,memory%20to%20facilitate%20critical%20thinking.

I also recommend Proust and the Squid on this topic which I believe from your article you will also enjoy. Though its 20 old and that’s a hit on a book like that… more so than Copperfield! Thanks for the read.

https://g.co/kgs/bU18AV