I saw this ad the other day, asking me what was the death which most affected me:

That is easy for me to answer.

I saw this ad the other day, asking me what was the death which most affected me.

That is easy.

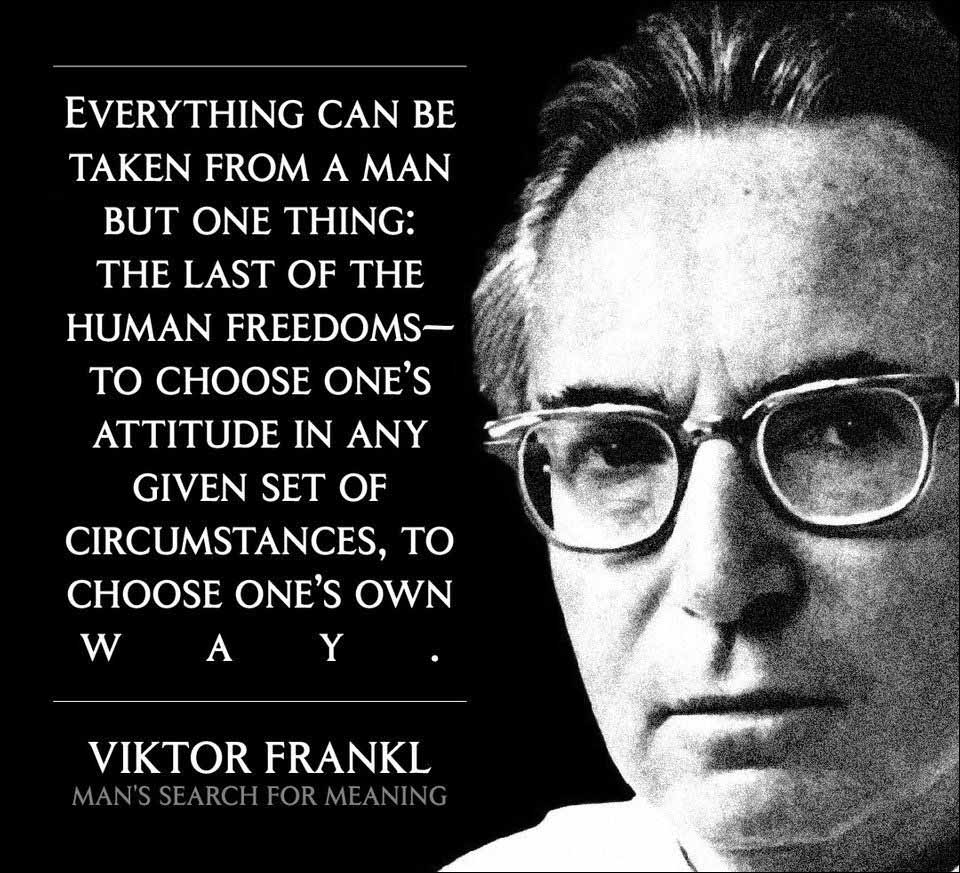

It was the death of Viktor Frankl on September 2, 1997.

I was floored.

His book Man’s Search For Meaning was one of the most important books of the 20th century.

But let’s first examine who Viktor Frankl was not.

He was not Elie Wiesel.

Wiesel had embraced despair and nihilism after suffering in a Nazi death camp, as can be evidenced in his book Night. This always seemed to be giving up to me. Other teachers would teach his novel as an axiomatic truth: if you underwent this misery in a Nazi death camp, you would feel the same. Well, Victor endured what Elie did. And he didn’t give up hope for either our species or our future.*

So Viktor Frankl was just the opposite of Elie Wiesel. If Ellie Wiesel emerged from the Holocaust having given up on the idea of hope and goodness, Frankl didn’t.

Viktor Frankl was an Austrian Jew who variously worked as a neurologist, psychiatrist, philosopher, and author. When Hitler took over his country Frankl and his family were sent to Nazi death camps, and his parents, brother, and wife all died in the Holocaust. But Frankl survived. Not only that, he did not emerge a man broken in spirit proclaiming God dead and “the good, the true, and the beautiful” to be extinct, as Wiesel seemed to do. Frankl did just the opposite. He claimed that a person could choose to endure and find happiness, even in a death camp and afterwards. He was the anti-Wiesel. Frankl lived out his his optimistic message by developing his school of psychology “Logotherapy” and encouraging his patients to embrace a life worth living – the antithesis of despair. Suicide was the polar opposite of what Viktor Frankl stood for. His book Man’s Search for Meaning was hugely influential to me as a young man; it is not too much to say that it changed my life. And when Frankl died on September 2nd, 1997 it was as if the world shook underneath my feet.

We had lost a giant.

But I looked around to see what others had to say about Viktor Frankl’s passing back in 1997, and I did not find much.

Why?

Because three days earlier on August 31, 1997 something else dramatic and tragic had occurred: Diana, Princess of Wales, had died in an auto accident in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel in Paris, France after being aggressively pursued by paparazzi in chase vehicles. That tragic car crash took all the oxygen in the room, and there was not much left for the death of anyone else, no more how notable they might be.

Everyone was talking about the death of “Princess Di.” It was wall-to-wall news coverage that dominated the airwaves. As a result, nobody paid much attention to the passing of Viktor Frankl.

This was astounding to me.

I had paid next to no attention to Princess Diana or the British royal family when she was alive, although I knew who she was from all the celebrity-worship coverage she had received over the years. I knew Princess Di was supposedly the “people’s princess,” and for some reason millions of others (British and otherwise) very much cared about her. And when she died there was an outpouring of sympathy for her plight, and 24/7 coverage of her death. But I did not care much. Princess Diana from Great Britain? Why exactly, as an American, should I care? Other than her being a “princess,” why was she important?

In contrast, Viktor Frankl was a towering figure in psychology, specifically, and in human thought, generally. They will be reading Man’s Search for Meaning and discussing its ideas well into the future.

But I felt almost alone in this conviction.

Nobody cared about Viktor Frankl.

Everyone was fixated on the deadly car chase with Princess Di in a tunnel in France.

So that is the announcement of a death that devastated me, and the memory is vivid 24 years later.

For some reason, the shock of Frankl’s death has stayed with me. It takes first place as the death of a famous person which shocked or devastated me the most.

Second place goes to the suicide of Nirvana lead singer Kurt Cobain on April 5, 1994.

By itself his death did not register much. Rock and roll singers or actors dying of drugs or whatever was not more unusual back in the 1990s than it is today, and Cobain dying was a headline when I read with relative indifference. What did strike me, however, was how much of an impact Cobain’s suicide had on my students at the time.

I was a beginning teacher in a predominantly immigrant school in the Pico-Union area of Los Angeles, and many of our students were new arrivals to the United States and hardly spoke English. But the suicide of Kurt Cobain was devastating news at our working-class school. Many of these students themselves seemed to be on the verge of suicide, so distraught were they at the news of the Nirvana lead singer shooting himself in the head with a shotgun. I was amazed.

Why? What message had Cobain given them that his suicide was therefore so devastating?

I knew who Kurt Cobain was before his suicide. I had listened to his music.

But he did not register with me at all as an important symbol of the times. If Cobain brought some iconic message to the world with his band Nirvana, I did not receive it.

Did I miss something?

I wondered if I was in some subtle way out of tune with the time or my peers.

Why did so many identify with Princess Diana and Kurt Cobain?

Why didn’t more people care about Viktor Frankl?

I have no idea.

* It is the same nonsense when a Jewish American woman friend argued with me in the mid-1990s that she would never visit Germany because of the Holocaust, as if it the Third Reich had just fallen just yesterday instead of decades before her birth. Or those who would never tolerate Richard Wagner’s music, as if you cannot distinguish the music from Wagner’s 19th century anti-Semitism. This is best seen when Israeli conductor Daniel Berenboim tries to play Wagner’s operas in Tel Aviv, and hidden protesters in the audience disrupt the performance with noise makers. This is a form of small-minded censoriousness and contrariety which unfortunately is not rare, and is best seen nowadays online in “cancel culture.”

One Comment

Nikolai

I understand — I have the same issue. You have a great eye. Thank you for your article!