The purpose of this essay is to explain my ambivalence about science, and to identify how and why I best learn it. Science is important. You have to study it.

But I never enjoyed science classes in school. I enjoyed math even less.

I was a humanities person. I still am.

I would avoid science classes, and their boredom and pain, in youth.

But I go out of my way to learn about science as an adult. Over the past year I read Bill Bryson’s “A Short History of Nearly Everything” and “The Body: A Guide for Occupants,” for example. I enjoyed these two lengthy books, but there was something missing from them for me. There was so much information about the biological and physical world that my brain became overwhelmed. This and that and this and that and another thing. And then another thing. The kidneys and nervous system and bacterial infection; and the big bang and plate tectonics and gravity and so much else: it added up to an enormous amount of information. My eyes glazed over. I am glad to have read these two books, but after so much effort, little of it has stayed with me a year later, I realize. I look back and remember the subjects of whole chapters, but I can’t remember much else. So many details. How much did I really learn? The mass of facts I was presented about the human body which only a few stayed with me? The physics, chemistry, geology, and biology? All the minutiae?

Which is all very important. But science by itself seems to me hermetic and self-absorbed. I don’t care too much about hormones and and nerve receptors. But I do care about love and pleasure. And so if you link the science of hormones and sexual reproduction with the drama of courtship and romantic desire, now I am interested. If you explain to me the physicochemical basis for Jane Austin’s “Pride and Prejudice,” I am all ears. I care about the lovers Elizabeth and Darcy and what happens between them. You can’t really understand love and sex without understanding the production of testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone in the body, or the operation of dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin (attraction, attachment, and pleasure) in the brain. Young lovers are more than just hormones with feet, or at least sometimes they are, but to ignore the hormones is plain silly.

So one needs to understand the raw science. And one also needs to understand how the science interacts daily with how people actually live. Too much science in my own formal education was delivered in a way which was science for the sake of science. I never saw the point to so much minutiae. Most scientists I have known are fascinated with the minutiae of science. I was not. Past a point, it bored me.

But justice, romance, valor, sacrifice, suffering, endurance, transcendence — all these interested me. Wars and revolutions, tragedy and triumph, villains and heroes; the past and the present, change and continuity, consensus and contention; life and death, love and hate, salvation and betrayal — I could spend a lifetime studying this, and I have. In childhood I found lots to learn in literature and history, and I have been studying them ever since. The humanities is what interests me. Human life. Almost all the miscellany of humanity interests me. Because I’m human.

Yet I understand the importance of science because it explains human life, at least some of the time, and at least indirectly. I have learned where I could. Where the science and math are explicitly linked with human life and human happiness is where I have had the easiest time.

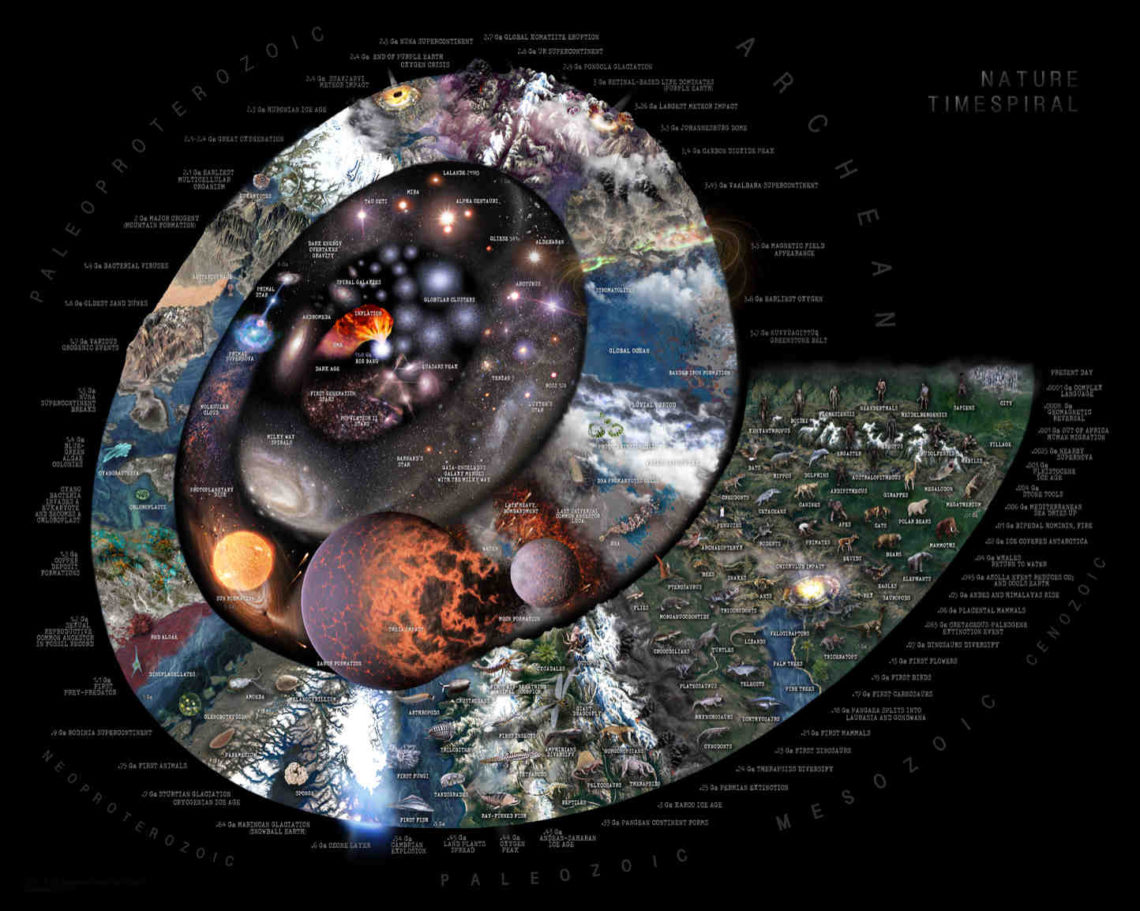

That is why I have found “Big History” particularly enriching. When you look at huge swathes of world history in a multidisciplinary approach based on combining numerous disciplines from science and the humanities, it all begins to make sense. Seeing the integrated story of history with the development of the natural and the human worlds together, that is important.

Why do we segregate the different subjects so much? Why is math and science always taught so separately from literature and history in schools?

Why is literature a different class from history?

I have long experience in teaching combined English-history classes. Personally, I don’t see much of a difference between the study of literature and history. History is simply the study of individual and collective stories from the past, which happen to be true. And imaginative literature is lying — i.e. fiction, the making up of stories — used to get at deeper human truths than can be found in history. Language and stories, history and literature: it is all narrative.

But most history teachers I have met do not enjoy writing in their own lives, or in reading “serious literature” for fun. They like history so they study and teach history. Similarly, most English teachers I have known do not read or study history. They don’t particularly enjoy it. They enjoy reading fiction, mostly, and writing about it. So they became English teachers.

I like both. Where I start and stop as an English or history teacher I cannot tell. They are pretty much the same thing for me. The humanities. I have spent almost three decades teaching humanities courses.

But go to any large high school or university and the comparative literature and history departments are separate fiefdoms with little interplay. Much of this is bureaucratic. Separate departments have separate staff who have their own budgets and personnel. The bureaucratic structure of schools serves to keep the subjects separate: different departments have their own turf struggles and political preoccupations. The result is literature and history teachers don’t come together much.

And the humanities teachers have even less interaction with their math and science counterparts.

But these divisions of scholarship are artificial distinctions not borne out in the real world. The scientific world directly informs the context in which the humanities operate in, and human life and science should be intimately acquainted.

It is all one. An essential unity in diversity.

At least that is how it should be.

So I try, wherever possible, to see the single story of human knowledge. To diminish tribal fixations. To appreciate the big picture.

Big history is so good. So fruitful. It does not negate any of the smaller studies I have made in Russian literature, American history, Baroque music, or whatever. In fact, it illuminates this learning and places it properly in the larger context.

I recommend “big history” —

In fact, if you cannot understand and appreciate the big picture, what is the point of all your smaller, more parochial learning? How much do you really know of our story? The study of humans, and their forerunners over time, on our planet? And of the history of our galaxy and elsewhere?

Are you so busy with specific minutiae that you cannot stand back and understand the larger story?

How much then do you really know?

One Comment

LE

Great stuff! Couldn’t agree more.